Ed.Ledoux

Ed.Ledoux- Posts : 3360

Join date : 2012-01-04

April Fools

April Fools

Sat 17 Jun 2017, 10:48 pm

Trying to nail down Lee whereabouts in early April;

I will start with April 6th

Lee gets fired from job at JCS April Fools day and is unemployed as of that friday.

April 7th

Marina is asked by Ruth if she wants to move in with Ruth. This is from secondary sources, need cite.

April 8th

"Monday, April 8, Lee applied for another job at the Texas Employment Commission, two days after Ruth Paine invited Marina to live with her “rather than return to Russia.” -JVB

She is half correct, either the TEC was notified of the firing by Lee or JCS it seems on the 8th the first work day after Lee is fired.

His card is then reactivated,

He then is at the TEC on the 11th which is noted on the 12th which Lee is supposedly also at the TEC again:

Note:

There is still is a Hidell design firm in Dallas(?) Carro[size=undefined]llton.

Wm. J. Hidell, designed Gladoaks estate for Murchison where a party was thrown on November 21, 1963. Hoover, Nixon and other right-wingers were in attendance, according to Madeline Brown.

[/size]

History

Hidell & Associates Architects has been providing superior architectural design solutions, nation wide, for more than 50 years. Conceived in 1948 as a partnership between architects William Hidell, II and Pete Decker, Hidell & Decker Architects designed & constructed commercial and industrial projects until 1952. From 1952-1979, William Hidell, II continued his work as a sole proprietorship under the firm name of William H. Hidell Architects. The firm was incorporated in 1979 as Hidell Architects, Inc. and began to take a special interest in the design and development of libraries under the new leadership of William Hidell, III. In 1995, Hidell Architects, Inc. became known as Hidell & Associates Architects, and the firm's present day name.

Then Jeanne shouted excitedly again: “look, there is an inscription here.” It read: ‘To my dear friend George from Lee.’ and the date follow [sic] — April 1963, at the time when we were thousands of miles away in Haiti. I kept looking at the picture and the inscription deeply moved [me], my thoughts going back when Lee was alive.

https://www.google.com/search?q=April+7%2C+1963%2C+while+de+Mohrenschildt+is+hanging+out+with+Oswald&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8#

Robert Oswald said:

April 7 is my birthday. On April 7, 1963,

Lee took his newly purchased rifle out to the

home of Gen. Edwin Walker with the intention

of shooting him.

April 10 is the birthday of my son, Robert

Edward Lee Oswald. On April 10, 1963, Lee

again went out to General Walker s home, stood

there in the darkness, and fired through a window

at the General.

https://archive.org/stream/nsia-OswaldRobert/nsia-OswaldRobert/Oswald%20Robert%2017_djvu.txt

Anyone have any Oswald info in early April?

Cheers, Ed

I will start with April 6th

Lee gets fired from job at JCS April Fools day and is unemployed as of that friday.

April 7th

Marina is asked by Ruth if she wants to move in with Ruth. This is from secondary sources, need cite.

April 8th

"Monday, April 8, Lee applied for another job at the Texas Employment Commission, two days after Ruth Paine invited Marina to live with her “rather than return to Russia.” -JVB

She is half correct, either the TEC was notified of the firing by Lee or JCS it seems on the 8th the first work day after Lee is fired.

His card is then reactivated,

He then is at the TEC on the 11th which is noted on the 12th which Lee is supposedly also at the TEC again:

Note:

There is still is a Hidell design firm in Dallas(?) Carro[size=undefined]llton.

Wm. J. Hidell, designed Gladoaks estate for Murchison where a party was thrown on November 21, 1963. Hoover, Nixon and other right-wingers were in attendance, according to Madeline Brown.

[/size]

History

Hidell & Associates Architects has been providing superior architectural design solutions, nation wide, for more than 50 years. Conceived in 1948 as a partnership between architects William Hidell, II and Pete Decker, Hidell & Decker Architects designed & constructed commercial and industrial projects until 1952. From 1952-1979, William Hidell, II continued his work as a sole proprietorship under the firm name of William H. Hidell Architects. The firm was incorporated in 1979 as Hidell Architects, Inc. and began to take a special interest in the design and development of libraries under the new leadership of William Hidell, III. In 1995, Hidell Architects, Inc. became known as Hidell & Associates Architects, and the firm's present day name.

Then Jeanne shouted excitedly again: “look, there is an inscription here.” It read: ‘To my dear friend George from Lee.’ and the date follow [sic] — April 1963, at the time when we were thousands of miles away in Haiti. I kept looking at the picture and the inscription deeply moved [me], my thoughts going back when Lee was alive.

https://www.google.com/search?q=April+7%2C+1963%2C+while+de+Mohrenschildt+is+hanging+out+with+Oswald&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8#

Robert Oswald said:

April 7 is my birthday. On April 7, 1963,

Lee took his newly purchased rifle out to the

home of Gen. Edwin Walker with the intention

of shooting him.

April 10 is the birthday of my son, Robert

Edward Lee Oswald. On April 10, 1963, Lee

again went out to General Walker s home, stood

there in the darkness, and fired through a window

at the General.

https://archive.org/stream/nsia-OswaldRobert/nsia-OswaldRobert/Oswald%20Robert%2017_djvu.txt

Anyone have any Oswald info in early April?

Cheers, Ed

Re: April Fools

Re: April Fools

Sat 17 Jun 2017, 11:10 pm

Ed, nothing to give you, but if Oswald went to the TEC on the 8th, he would have needed to update his home address.

Is there a TEC record showing he lived at 214 Neely?

Is there a TEC record showing he lived at 214 Neely?

_________________

Australians don't mind criminals: It's successful bullshit artists we despise.

Lachie Hulme

-----------------------------

The Cold War ran on bullshit.

Me

"So what’s an independent-minded populist like me to do? I’ve had to grovel in promoting myself on social media, even begging for Amazon reviews and Goodreads ratings, to no avail." Don Jeffries

"I've been aware of Greg Parker's work for years, and strongly recommend it." Peter Dale Scott

https://gregrparker.com

Re: April Fools

Re: April Fools

Sat 17 Jun 2017, 11:14 pm

There is also this...

His Father William H Hidell, Sr had three brothers, Henry, Charles and Alex. The family had lost contact with Alex decades in the past and he was believed to live on the west coast and in the yachting business.

http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/FBI%20Records%20Files/105-82555/105-82555%20Section%20084/84c.pdf

His Father William H Hidell, Sr had three brothers, Henry, Charles and Alex. The family had lost contact with Alex decades in the past and he was believed to live on the west coast and in the yachting business.

http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/FBI%20Records%20Files/105-82555/105-82555%20Section%20084/84c.pdf

_________________

Australians don't mind criminals: It's successful bullshit artists we despise.

Lachie Hulme

-----------------------------

The Cold War ran on bullshit.

Me

"So what’s an independent-minded populist like me to do? I’ve had to grovel in promoting myself on social media, even begging for Amazon reviews and Goodreads ratings, to no avail." Don Jeffries

"I've been aware of Greg Parker's work for years, and strongly recommend it." Peter Dale Scott

https://gregrparker.com

Re: April Fools

Re: April Fools

Sun 18 Jun 2017, 1:41 am

Ed:Ed. Ledoux wrote:Anyone have any Oswald info in early April?

Cheers, Ed

I'll put up what Walt Brown says in his chronology during this time concerning Oswald in a series of posts.

_________________________________________________

April 1, 1963— time unstated; Dallas, Texas;

M. Waldo George, the manager of the apartments at 214 Neeley Street, collected $ 60 in cash from Lee Oswald, which would cover the rent “for the month of April 1963 to and including May 2, 1963.”

“Shortly after this occasion the downstairs tenants, Mr. and Mrs. George B. Gray, called me and informed me that the man in the upstairs apartment was beating his wife. I made no inquiry into the subject matter.”

“Two or three days later, myself and Mrs. George called on the Oswalds in their apartment and invited them to attend Gaston Avenue Baptist Church with us. He informed me and Mrs. George that he attended the Russian Orthodox Church although they were not regular in their attendance, because they had to depend on their friends to take them.”

“During this visit Oswald stated that he had met his wife while he was serving in the United States Marines as a guard at the United States Embassy in Russia, and had married his wife in Russia. I made direct inquiry of him as to whether he had any difficulty in getting out of Russia with his wife and he said that he had had no difficulty whatsoever.”

“Neither myself or Mrs. George saw Oswald again at any time thereafter. Oswald did not pay rent for the succeeding rental period of May 2 through June 2, 1963. Because my attention was diverted by other matters, I did not go by the apartment to collect the rent for that period until several days after May 2, 1963. When I arrived at the apartment I found it vacant. (Affidavit of M. Waldo George, 11H 156) Note: Oswald may have found it a convenient explanation of his marriage to a Russian woman by suggesting he had been an Embassy guard, but it is still Lee Oswald, quick with the bizarre lie, at work. Beyond that, Oswald had left the Neely Street apartment on April 24, 1963, and at roughly the same time, Ruth Paine took in Marina Oswald as a house-guest and Russian tutor until such time as Lee Oswald found work in New Orleans and Marina could join him there.

April, 1963— specific time unknown and certainly not sought, CST— Dallas, Texas.

Robert Adrian Taylor, an employee at Jack’s Super Shell gas station, believed he had a gun transaction with Lee Oswald.

Oswald, along with another male, identity unknown, needed an automotive generator repair but lacked funds; a deal was struck and the gun, a Springfield bolt action, .30-06, which Taylor admittedly possessed and hunted with, was taken from the trunk of the vehicle and used as barter for the repair.

In an FBI Report dated May 19, 1964— a summary report, and not an FD-302 which would contain an agent’s name, it is stated, “TAYLOR advised that on November 23, 1963, he was watching television and, upon viewing LEE HARVEY OSWALD, commented to his wife, ‘Say, that looks like the guy I bought the .30-06 from.’ He stated, however, he cannot be positively sure the man who sold him the rifle was OSWALD. He stated that he feels that it was OSWALD since, upon viewing OSWALD on television, he immediately thought of this rifle, and, at that instant, thought OSWALD was the man who sold the weapon to him.” (FBI Report, 26H, 458-459)

Later in the same report, Taylor suggests that the man he believed to be Oswald may have returned to the station as a passenger in a vehicle driven by a woman, but since Oswald still owed him two boxes of ammunition, he had reason to doubt that it was Oswald on the second occasion.

Here’s what the Warren Report said about all of this: Another allegation relating to the possible ownership of a second rifle by Oswald comes from Robert Adrian Taylor, a mechanic at a service station in Irving. Some 3 weeks after the assassination, Taylor reported to the FBI that he thought that, in March or April of 1963, a man he believed to be Oswald had been a passenger in an automobile that stopped at his station for repairs; since neither the driver nor the passenger had sufficient funds for the repair work, the person believed to be Oswald sold a U.S. Army rifle to Mr. Taylor, using the proceeds to pay for the repairs. However, a second employee at the service station,[ there was no second employee present at the time of this transaction] who recalled the incident believed that, despite a slight resemblance, the passenger was not Oswald. Upon reflection, Taylor himself stated that he is very doubtful Taylor himself stated that he is very doubtful that the man was Oswald.” (Warren Report, p. 318, U.S. Government Printing Office edition)

Straight-up: It’s a bold-face lie. The ‘second employee’ was Glen Emmett Smith, who DID testify before the Warren Commission, while Taylor, who purchased the gun and identified the seller to the FBI as Lee Oswald, did not. (Warren Commission deposition of Smith: 10H 399-405) Smith did not recall the incident except to overhear it being told by Taylor to FBI S/ A Morris J. White, who is not mentioned nor cited in the FBI Summary Report of the incident, dated May 19, 1964, and which came at the request of the Warren Commission in a letter dated April 30, 1964— after Glen E. Smith’s testimony. Further, Smith testified he began his employment at the gas station on April 25, 1963— the day after Lee Oswald rode a bus to New Orleans, so he could not have been a witness to the transaction and thereafter denied the resemblance to Oswald.

Re: April Fools

Re: April Fools

Sun 18 Jun 2017, 1:45 am

Continuing...

April 1, 1963— time unstated; Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald changes his address on his Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall records to Post Office Box 2915 in Dallas; inasmuch as he was given notice of imminent termination from Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall, (his last day was April 6 [oddly, an overtime Saturday], and he was fired— he did not quit), it is possible that this was the time he learned of his termination. (John F. “Jay” Harrison” Genealogical Archives) Note: This seemingly unremarkable event may have also provided the “bridge” between the March 31 photos and the April 10, 1963 attempt on General Walker, as Oswald, now a lame-duck employee, could use his remaining time to make copies of the March 31 “backyard photographs,” as well as of surveillance photos he is believed to have taken of the Walker residence.

April 2, 1963— time unstated, although event would occur in the evening, CST; Dallas, Texas. Ruth Paine invites Marina and Lee Oswald to dinner, and it on this occasion that Michael Paine met Lee Oswald for the first time. (Testimony of Ruth Paine, 2H 450) Note: Ruth Paine would later testify that Michael drove to pick up Marina Oswald and Lee Oswald. This for the most-part casual event would allow Michael Paine, on the evening of November 22, to recall the building— 214 W. Neely Street— when he was shown a “backyard photograph” and asked if he had any knowledge of where it had been taken. (Testimony of Ruth Paine, 2H 480; Michael Paine’s “clapboard recognition” testimony is at 9H 444) April 2, 1963---time not specified, Huntsville Prison, Texas. On the same evening that Michael Paine met Lee Oswald for the first time, Juanita Dale Phillips, whose stage name was “Candy Barr,” was released from Huntsville Prison after serving three years and four months of a fifteen year sentence for narcotics possession (marijuana). Ms. Phillips was met by Mr. and Mrs. Abe Weinstein, Jack Ruby’s competitors in Dallas, and taken home. (Austin American, April 2, 1963, pages 24 and 25.) “Sometime in the spring of 1963”— Michael Paine meets Lee Oswald for the first time; Michael noted that Ruth Paine had met the Oswalds earlier at a party hosted by Everett Glover which, he, Michael Paine, did not attend. He added that Ruth then invited Lee and Marina Oswald to dinner, and cited the date as April 10, 1963— the night General Edwin Walker was shot at. He is corrected by Warren Commission staff counsel Wesley Liebeler, who tells him the dinner was on April 2, 1963. (Testimony of Michael Paine, 2H 393, 402) Note: Michael Paine’s best memory of the event is that Lee Oswald spoke rudely and sharply to Marina, in the presence of dinner guests. (Testimony of Michael Paine, 2H 422) Note: In a subsequent deposition before Counsel Wesley Liebeler (unlike the testimony before the Commission cited herein), Paine was asked if General Walker was discussed at the first meeting between Lee Oswald and Paine. Paine answered, “Yes; I think we did discuss him in passing.” (Deposition of Michael Ralph Paine, 11H 399) This would tend to suggest that the dinner WAS on April 2, 1963, and not the night Oswald left the note for Marina— April 10— when Michael Paine could NOT have met Oswald unless he was driving the getaway vehicle seen by General Walker— see entry for April 10, 1963) Paine was also asked “Did Oswald ever indicate to you in any way that he had been involved in the attempt on General Walker’s life?” Paine answered: “Not that I remember at all— nothing whatsoever. I think the only thing he did— the only thing that I can remember now, was that he seemed to have a smile in regard to that person. It was inscrutable— I didn’t know what he was smiling about— I just thought perhaps it was— the guy assumed it was rapport for a person who was an extreme proponent of patriotism or something.” (Deposition of Michael Ralph Paine, 11H 399) This is probably a steno error and where it states “it was— the guy” it should read, “it was— that I”; beyond that, given what Paine knew about Oswald’s political thinking, this answer is absurd; it’s also ridiculous since it revolves around the first meeting between Michael Paine and Lee Oswald on April 2, 1963, eight days before the attempt on General Walker. Paine further testified that after April 2, 1963, he did not see Lee Oswald again until after his return to Texas from “New Orleans” (via Mexico), which would be early October, 1963, when Walker was not as controversial a topic. It remains a curiosity that the Warren Commission would ask Michael Paine when the dinner was held, and when his answer contradicted a central fact— the Walker shooting of April 10— Paine was told he was wrong, and he was corrected. Right or wrong, if Paine had said the dinner took place on Christmas Day, 1963, a month and a day after Oswald was publicly executed, his answer should have been allowed to stand, unchallenged. No individual was allowed to question the Warren Commission’s perceptions, although a lot of people have done so since they went out of business.

April 1, 1963— time unstated; Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald changes his address on his Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall records to Post Office Box 2915 in Dallas; inasmuch as he was given notice of imminent termination from Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall, (his last day was April 6 [oddly, an overtime Saturday], and he was fired— he did not quit), it is possible that this was the time he learned of his termination. (John F. “Jay” Harrison” Genealogical Archives) Note: This seemingly unremarkable event may have also provided the “bridge” between the March 31 photos and the April 10, 1963 attempt on General Walker, as Oswald, now a lame-duck employee, could use his remaining time to make copies of the March 31 “backyard photographs,” as well as of surveillance photos he is believed to have taken of the Walker residence.

April 2, 1963— time unstated, although event would occur in the evening, CST; Dallas, Texas. Ruth Paine invites Marina and Lee Oswald to dinner, and it on this occasion that Michael Paine met Lee Oswald for the first time. (Testimony of Ruth Paine, 2H 450) Note: Ruth Paine would later testify that Michael drove to pick up Marina Oswald and Lee Oswald. This for the most-part casual event would allow Michael Paine, on the evening of November 22, to recall the building— 214 W. Neely Street— when he was shown a “backyard photograph” and asked if he had any knowledge of where it had been taken. (Testimony of Ruth Paine, 2H 480; Michael Paine’s “clapboard recognition” testimony is at 9H 444) April 2, 1963---time not specified, Huntsville Prison, Texas. On the same evening that Michael Paine met Lee Oswald for the first time, Juanita Dale Phillips, whose stage name was “Candy Barr,” was released from Huntsville Prison after serving three years and four months of a fifteen year sentence for narcotics possession (marijuana). Ms. Phillips was met by Mr. and Mrs. Abe Weinstein, Jack Ruby’s competitors in Dallas, and taken home. (Austin American, April 2, 1963, pages 24 and 25.) “Sometime in the spring of 1963”— Michael Paine meets Lee Oswald for the first time; Michael noted that Ruth Paine had met the Oswalds earlier at a party hosted by Everett Glover which, he, Michael Paine, did not attend. He added that Ruth then invited Lee and Marina Oswald to dinner, and cited the date as April 10, 1963— the night General Edwin Walker was shot at. He is corrected by Warren Commission staff counsel Wesley Liebeler, who tells him the dinner was on April 2, 1963. (Testimony of Michael Paine, 2H 393, 402) Note: Michael Paine’s best memory of the event is that Lee Oswald spoke rudely and sharply to Marina, in the presence of dinner guests. (Testimony of Michael Paine, 2H 422) Note: In a subsequent deposition before Counsel Wesley Liebeler (unlike the testimony before the Commission cited herein), Paine was asked if General Walker was discussed at the first meeting between Lee Oswald and Paine. Paine answered, “Yes; I think we did discuss him in passing.” (Deposition of Michael Ralph Paine, 11H 399) This would tend to suggest that the dinner WAS on April 2, 1963, and not the night Oswald left the note for Marina— April 10— when Michael Paine could NOT have met Oswald unless he was driving the getaway vehicle seen by General Walker— see entry for April 10, 1963) Paine was also asked “Did Oswald ever indicate to you in any way that he had been involved in the attempt on General Walker’s life?” Paine answered: “Not that I remember at all— nothing whatsoever. I think the only thing he did— the only thing that I can remember now, was that he seemed to have a smile in regard to that person. It was inscrutable— I didn’t know what he was smiling about— I just thought perhaps it was— the guy assumed it was rapport for a person who was an extreme proponent of patriotism or something.” (Deposition of Michael Ralph Paine, 11H 399) This is probably a steno error and where it states “it was— the guy” it should read, “it was— that I”; beyond that, given what Paine knew about Oswald’s political thinking, this answer is absurd; it’s also ridiculous since it revolves around the first meeting between Michael Paine and Lee Oswald on April 2, 1963, eight days before the attempt on General Walker. Paine further testified that after April 2, 1963, he did not see Lee Oswald again until after his return to Texas from “New Orleans” (via Mexico), which would be early October, 1963, when Walker was not as controversial a topic. It remains a curiosity that the Warren Commission would ask Michael Paine when the dinner was held, and when his answer contradicted a central fact— the Walker shooting of April 10— Paine was told he was wrong, and he was corrected. Right or wrong, if Paine had said the dinner took place on Christmas Day, 1963, a month and a day after Oswald was publicly executed, his answer should have been allowed to stand, unchallenged. No individual was allowed to question the Warren Commission’s perceptions, although a lot of people have done so since they went out of business.

Re: April Fools

Re: April Fools

Sun 18 Jun 2017, 1:53 am

Continuing...

April 5, 1963— time unstated, CST; Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald puts the date 5 IV 63 on a print of a photo from the backyard, with him holding a rifle and newspapers, and wearing a pistol in a holster. The photo, along with English/ Russian phonograph records loaned to Oswald by George DeMohrenschildt, was mailed to DeMohrenschildt’s address, shortly before he left the United States for Haiti. The package was stored, according to DeMohrenschildt, and the photo was only discovered in 1967. (John F. “Jay” Harrison” Genealogical Archives) Note: This particular “backyard photo” had the notation, in Russian, “Ha ha ha, hunter of fascists,” and from an examination of the handwriting, compared to other samples published or privately owned, it is highly likely that Marina Oswald wrote the caption. (editor’s hypothesis, which, if correct, would not have seemed nearly as funny a few days later when, it is alleged, the “hunter of fascists” took a shot at General Edwin Walker, U.S. Army, Resigned.) It is also to be recalled, at occasional points through this narrative, that when Marina Oswald was first taken to the Dallas Police station, she denied ever having seen Oswald’s rifle— despite the fact that she photographed it. This created a serious Catch-22 for the Warren Commission, as they had Marina admitting to important evidence against her husband, with respect to a gun that she never saw, excepting the inch or so visible* at the butt-end of the blanket. (*) Michael Paine dealt with that blanket, thinking it was tent poles. If one inch of the rifle was visible, even Michael Paine probably would have concluded it was not tent poles or camping gear.

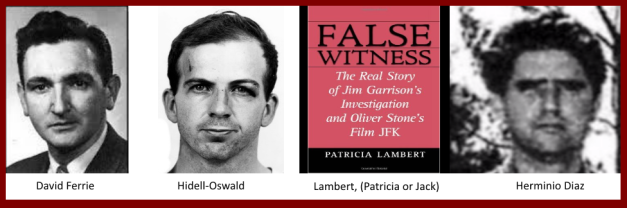

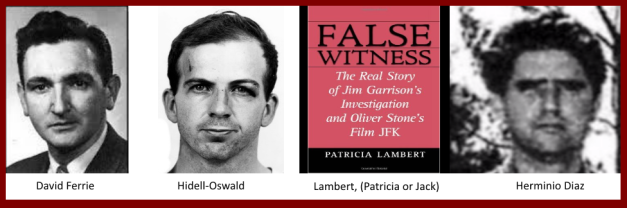

April 6, 1963— according to the testimony of Marguerite Oswald, this is the last day of employment of Lee Oswald at Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall— a Saturday. (Testimony of Marguerite Oswald 1H 218) (see also time cards for employment, published as CE 1855 in 23H 624-625) Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall photo department manager also indicates that April 6, 1963 was Oswald’s last day. (Deposition of John G. Graef, 10H 178) That data, however, defies logic, as Saturday work was overtime, and by that point in time, Oswald’s work was viewed as lousy, and Jaggers was not likely to pay him overtime to do virtually nothing correct on his last day of work. Either way, the end of the job coincides with alleged “Walker” preparation, and within less than three weeks, Oswald was in New Orleans. Dennis Ofstein would testify, “… he mentioned the last day he was with Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall— I asked him what he was going to do, where he would go to work, and he said he didn’t know. He liked the type of work at the company and that he would like to stay with this type of work and he would look around and if he didn’t find anything else, he could always go back to the Soviet Union, and sort of laughed about it. (Deposition of Dennis Hyman Ofstein, 10H, 203) Note: John Graef, photo department director at Jaggers, would testify, “… in the course of carrying these jobs through and back in the darkroom, I began to hear vague rumors of friction between him and the other employees… I began hearing that— or began noticing— that very few people liked him. He was very difficult to get along with… Lee was not one to make friends… Then, we’ll say his personality began to come out… there was an incident about a Russian newspaper deal… andhe said, ‘I studied Russian in Korea,’; but mostly, it was Oswald’s poor work product: “more and more he was being relied upon to produce this exact work and there were too many times— it was his mistakes were above normal. He was making too many mistakes… Well, my impression of his mistakes were somehow that he just couldn’t manage to avoid them. It wasn’t that he lacked industry or didn’t try… I think he just couldn’t— he somehow couldn’t manage to handle work that was exact.” (Deposition of John G. Graef, 10H 186-188) Note: John Armstrong cited House Select Committee Document #006795 which notes that on the same day, a flight plan was filed for air travel between New Orleans and Garland, Texas. The pilot was listed as D. Ferrie, and the three passengers were Diaz, Lambert (Clay Shaw alias?) and Hidell (see John Armstrong, Harvey and Lee: How the CIA Framed Oswald, pp. 505 and 519) Question: If Oswald could not manage to handle work that was exact, and didn’t have the skills to drive, HOW did he take a war surplus rifle and perform a task that required exactitude far above and far beyond the mundane chores he was unable to perform?

April 6, 1963— time unstated, presumably p.m., Dallas, Texas; On the date of his termination from Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall, Lee Oswald was given an invitation to visit Dennis Ofstein and his family; Ofstein, because of his abilities with the Russian language, was the closest thing to a friend Oswald had at Jaggers. As far as this written invitation to Oswald, “none whatsoever” was the response. (Deposition of Dennis Hyman Ofstein, 10H 198) April 7, 1963— Ruth Paine writes to Marina Oswald, offering her shelter in the Paine home, but does not mail the letter. (Testimony of Ruth Paine, 2H 449)* additional confirmation of “not sent” (Testimony of Ruth Paine, 2H 502) Note: See Ruth Paine entry for April 8, for which there was no testimony.

April 8, 1963— Ruth Paine visited Marina Oswald at the Neely Street residence; Lee Oswald, although unemployed, was not present. (FBI report of S/ As Bardwell Odum and James Hosty, November 28, 1963; CE 2124, 24H 692)

April 8, 1963— time unstated, CST— Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald reported to the Texas Employment Commission “seeking employment; he having lost his position with Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall.” (Affidavit of Helen P. Cunningham, June 11, 1964, 11H 478) Note: Two days later is the alleged “Walker incident,” and two days following that, Oswald will again visit the Texas Employment Commission. Perhaps he now considered himself an unemployed and not easily-employed, based on his failure in his new attempted career move: sniper.

April 5, 1963— time unstated, CST; Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald puts the date 5 IV 63 on a print of a photo from the backyard, with him holding a rifle and newspapers, and wearing a pistol in a holster. The photo, along with English/ Russian phonograph records loaned to Oswald by George DeMohrenschildt, was mailed to DeMohrenschildt’s address, shortly before he left the United States for Haiti. The package was stored, according to DeMohrenschildt, and the photo was only discovered in 1967. (John F. “Jay” Harrison” Genealogical Archives) Note: This particular “backyard photo” had the notation, in Russian, “Ha ha ha, hunter of fascists,” and from an examination of the handwriting, compared to other samples published or privately owned, it is highly likely that Marina Oswald wrote the caption. (editor’s hypothesis, which, if correct, would not have seemed nearly as funny a few days later when, it is alleged, the “hunter of fascists” took a shot at General Edwin Walker, U.S. Army, Resigned.) It is also to be recalled, at occasional points through this narrative, that when Marina Oswald was first taken to the Dallas Police station, she denied ever having seen Oswald’s rifle— despite the fact that she photographed it. This created a serious Catch-22 for the Warren Commission, as they had Marina admitting to important evidence against her husband, with respect to a gun that she never saw, excepting the inch or so visible* at the butt-end of the blanket. (*) Michael Paine dealt with that blanket, thinking it was tent poles. If one inch of the rifle was visible, even Michael Paine probably would have concluded it was not tent poles or camping gear.

April 6, 1963— according to the testimony of Marguerite Oswald, this is the last day of employment of Lee Oswald at Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall— a Saturday. (Testimony of Marguerite Oswald 1H 218) (see also time cards for employment, published as CE 1855 in 23H 624-625) Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall photo department manager also indicates that April 6, 1963 was Oswald’s last day. (Deposition of John G. Graef, 10H 178) That data, however, defies logic, as Saturday work was overtime, and by that point in time, Oswald’s work was viewed as lousy, and Jaggers was not likely to pay him overtime to do virtually nothing correct on his last day of work. Either way, the end of the job coincides with alleged “Walker” preparation, and within less than three weeks, Oswald was in New Orleans. Dennis Ofstein would testify, “… he mentioned the last day he was with Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall— I asked him what he was going to do, where he would go to work, and he said he didn’t know. He liked the type of work at the company and that he would like to stay with this type of work and he would look around and if he didn’t find anything else, he could always go back to the Soviet Union, and sort of laughed about it. (Deposition of Dennis Hyman Ofstein, 10H, 203) Note: John Graef, photo department director at Jaggers, would testify, “… in the course of carrying these jobs through and back in the darkroom, I began to hear vague rumors of friction between him and the other employees… I began hearing that— or began noticing— that very few people liked him. He was very difficult to get along with… Lee was not one to make friends… Then, we’ll say his personality began to come out… there was an incident about a Russian newspaper deal… andhe said, ‘I studied Russian in Korea,’; but mostly, it was Oswald’s poor work product: “more and more he was being relied upon to produce this exact work and there were too many times— it was his mistakes were above normal. He was making too many mistakes… Well, my impression of his mistakes were somehow that he just couldn’t manage to avoid them. It wasn’t that he lacked industry or didn’t try… I think he just couldn’t— he somehow couldn’t manage to handle work that was exact.” (Deposition of John G. Graef, 10H 186-188) Note: John Armstrong cited House Select Committee Document #006795 which notes that on the same day, a flight plan was filed for air travel between New Orleans and Garland, Texas. The pilot was listed as D. Ferrie, and the three passengers were Diaz, Lambert (Clay Shaw alias?) and Hidell (see John Armstrong, Harvey and Lee: How the CIA Framed Oswald, pp. 505 and 519) Question: If Oswald could not manage to handle work that was exact, and didn’t have the skills to drive, HOW did he take a war surplus rifle and perform a task that required exactitude far above and far beyond the mundane chores he was unable to perform?

April 6, 1963— time unstated, presumably p.m., Dallas, Texas; On the date of his termination from Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall, Lee Oswald was given an invitation to visit Dennis Ofstein and his family; Ofstein, because of his abilities with the Russian language, was the closest thing to a friend Oswald had at Jaggers. As far as this written invitation to Oswald, “none whatsoever” was the response. (Deposition of Dennis Hyman Ofstein, 10H 198) April 7, 1963— Ruth Paine writes to Marina Oswald, offering her shelter in the Paine home, but does not mail the letter. (Testimony of Ruth Paine, 2H 449)* additional confirmation of “not sent” (Testimony of Ruth Paine, 2H 502) Note: See Ruth Paine entry for April 8, for which there was no testimony.

April 8, 1963— Ruth Paine visited Marina Oswald at the Neely Street residence; Lee Oswald, although unemployed, was not present. (FBI report of S/ As Bardwell Odum and James Hosty, November 28, 1963; CE 2124, 24H 692)

April 8, 1963— time unstated, CST— Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald reported to the Texas Employment Commission “seeking employment; he having lost his position with Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall.” (Affidavit of Helen P. Cunningham, June 11, 1964, 11H 478) Note: Two days later is the alleged “Walker incident,” and two days following that, Oswald will again visit the Texas Employment Commission. Perhaps he now considered himself an unemployed and not easily-employed, based on his failure in his new attempted career move: sniper.

Re: April Fools

Re: April Fools

Sun 18 Jun 2017, 2:09 am

Continuing...

April 10, 1963, prior to the events allegedly involving Lee Oswald and General Edwin Walker. The U.S. Navy announced that the nuclear submarine Thresher, with 129 men aboard, had been lost off the New England coast while making test dives after a recent overhaul at the Electric Boat complex. (Harold W. Chase and Allen H. Lehrman, eds., Kennedy and the Press; the News Conferences, p. 420) Note: It goes without saying that this news would clearly overshadow the “assassination attempt” on General Walker.

April 10, 1963— evening, CST, Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald eats dinner with Marina, and leaves their residence at 7: 00 or 7: 30 p.m. (Testimony of Marina Oswald 1H 37) Later, someone took a shot at General E. Walker, US Army, Resigned; Marina tells Warren Commission that Lee did not return from his typing class at Crozier Tech on schedule, and she became worried, walked into his room, and found a note with directions. “He only told me that he had shot at General Walker.” (Testimony of Marina Oswald 1H 16).

Marina added that Oswald claimed Walker was a fascist, and that the world would have been a better place if someone had killed Hitler. (Testimony of Marina Oswald 1H 16) In subsequent testimony, Marina indicates that Lee returned home at 11 p.m. Note: In James Martin’s testimony, Allan Dulles told Martin that the Walker event occurred on this date. (Statement by Commissioner Dulles during testimony of James H. Martin 1H 485) Questions: Did Marina notice anything odd about Oswald’s behavior at dinner? People planning to commit murder occasionally will behave outside of their traditional behavioral norms. Did Marina see Oswald take a rifle with him to “typing class”? There is no hint of it in her testimony, and not surprisingly, it is an unasked question. It seems unlikely that the question would not have been asked because Marina did not know what a rifle was. She knew. Had Marina made any protest, prior to April 10th, about the existence of the rifle and/ or the pistol? She would testify, after the assassination, that they were living in abject poverty, yet Oswald had enough resources to spray money around on his weapons collection. But did she make any such statement, or did she recall making any such statement, prior to the assassination? And was the abject poverty the sum and substance of her concern? Guns don’t kill people…. abject poverty does.

April 10, 1963— 9: 30 p.m. CST (time not precise). One shot was fired at Major General Edwin E. Walker, U.S. Army, Resigned, as he worked on his income tax returns while sitting near a window. He will telephone Robert Alan Surrey as well as the police, and Surrey will arrive within fifteen minutes, and overhear police conversation as well as press interviews given by Walker….

[There is a big big blurb on this I excluded.]

April 10, 1963— 9: 15 or 9: 30 p.m., CST, Dallas, Texas. Robert Alan Surrey arrives at the home of General Edwin A. Walker, U.S. Army, retired. Aware of people looking in windows on April 8 and the presence of tire prints outside, Surrey spends the evening at Walker’s home and the tire imprint evidence is sought on the morning of April 11. (Testimony of Robert Alan Surrey, 5H 440) Note: Upon Surrey’s arrival, Walker pointed to a hole in the wall and Surrey said, “Oh, you found a bug.” Surrey would also notice that Walker’s right forearm was bleeding slightly. No explanation is given for that.

April 10, 1963— 10: 00 p.m., CST— Dallas, Texas. Marina Oswald “suddenly” discovers a note written by Lee Oswald, which allegedly contained instructions as to what she should do in the event he is taken into police custody. The first item indicated, “Here is the Key to the post office box which is located in the main post office downtown on Ervay Street, the street where there is a drugstore where you always used to stand.” As it happens, the Post Office was at 400 N. Ervay Street (where Warren Commission depositions were taken in Dallas), and four blocks south of there was “Skillern’s Drugs” on the first floor of the Mercantile Bank Building. The fifth and seventh floors of that building were occupied by Hunt Oil Company. The Warren Commission Exhibit volumes begin on 16H 1, and the first item is “an unsigned note in Russian to Marina Oswald.” The contents of this note, when translated by my erstwhile Russian guest, pro-tem, of the editor of this Chronology (and therefore able to be translated by any number of people in close contact with law enforcement, c. 1963), strongly suggest that it was the “Walker note,” left for Marina. It seems an odd and almost bizarre coincidence that the very first item published in the “manual of Oswald’s guilt” was a note providing instructions for what a non-Russian-speaking woman should do on the odd chance that her husband was incarcerated or killed in some unstated event. It seems even more odd that no translation was created for that exhibit— because many other such exhibits are translated. Nor was any handwriting expert consulted to see if the note was written by Oswald— since it was known, via Marina, that she received the note. The note has a notation that looks like “D 30 Jue” on the upper right-hand corner in smallish script. I cannot place any meaning on it. (Commission Exhibit 1, 16H 1) That said, I asked my transient Russian visitor to review a good number of Oswald’s writings in Russian, and while she found a good number of grammatical errors, most commonly the omission of necessary commas, she paused while reading this first document— this possible “Walker note”— and asked how long the writer of the document had been in Russia. I told her, “Two-point-five years, and this was approximately one year AFTER his return.” She told me that Oswald’s Russian— as shown in the note— that beyond the absence of commas, there were a number of extremely well-made connections in words. The Russian language contains constructions “bl” and “b,” which, when they follow certain other letters, are silent, but they change the intonation and inflection of the letter just before them. Oswald had all of them correct, and it seems unlikely that he wrote the Walker note using a dictionary over the span of several days. “Look, here,” my guest said, “many Russians would not get this correct— or this word here— would not be spelled correctly.” She also added parenthetically that “a long, long time ago,” she saw a movie, in Russia, in the Russian language. It was a Russian movie, not an American movie with a Russian overdub, and it portrayed Oswald as, in her specific words, “a very strange man indeed.” I leave it to the reader to draw the necessary conclusions, but it seems bizarre in the extreme that someone who could not spell at all well in English (allegedly his native language) could nevertheless correctly spell difficult if not impossible Russian words. Addendum: Although the first exhibit is not attributed to Oswald, nor specifically to the Walker event, the events immediately following CE 1 are also Walker-related, except for one photo of Oswald, neck-up, in his Marine digs with a helmet, suggesting, of course that he knew how to kill. You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows…. Question: Why would there be a reference to a location where Marina “used to stand”? Finally: Much has been made of the “Walker note,” and Marina, investing all her energy to convict her husband for everything imaginable, made sure that the Warren Commission got the full treatment, with all of the possible “Walker thoughts,” including all of that which Oswald allegedly burned so it did not have to be produced, still had the energy to note that the photo with the hole where the license plate should have been HAD been an intact photo when she saw it. Sylvia Meagher, a first-generation assassination researcher (d. 1989), took an alternative view of the so-called Walker note, and her spin is that it had nothing to do with an assassination attempt on General Walker. Meagher’s only published work (beyond her indices) is Accessories After the Fact, and to this it day remains one of the Chronology editor’s “top five” recommendations (personal works, including this monster, excluded).

April 10, 1963, prior to the events allegedly involving Lee Oswald and General Edwin Walker. The U.S. Navy announced that the nuclear submarine Thresher, with 129 men aboard, had been lost off the New England coast while making test dives after a recent overhaul at the Electric Boat complex. (Harold W. Chase and Allen H. Lehrman, eds., Kennedy and the Press; the News Conferences, p. 420) Note: It goes without saying that this news would clearly overshadow the “assassination attempt” on General Walker.

April 10, 1963— evening, CST, Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald eats dinner with Marina, and leaves their residence at 7: 00 or 7: 30 p.m. (Testimony of Marina Oswald 1H 37) Later, someone took a shot at General E. Walker, US Army, Resigned; Marina tells Warren Commission that Lee did not return from his typing class at Crozier Tech on schedule, and she became worried, walked into his room, and found a note with directions. “He only told me that he had shot at General Walker.” (Testimony of Marina Oswald 1H 16).

Marina added that Oswald claimed Walker was a fascist, and that the world would have been a better place if someone had killed Hitler. (Testimony of Marina Oswald 1H 16) In subsequent testimony, Marina indicates that Lee returned home at 11 p.m. Note: In James Martin’s testimony, Allan Dulles told Martin that the Walker event occurred on this date. (Statement by Commissioner Dulles during testimony of James H. Martin 1H 485) Questions: Did Marina notice anything odd about Oswald’s behavior at dinner? People planning to commit murder occasionally will behave outside of their traditional behavioral norms. Did Marina see Oswald take a rifle with him to “typing class”? There is no hint of it in her testimony, and not surprisingly, it is an unasked question. It seems unlikely that the question would not have been asked because Marina did not know what a rifle was. She knew. Had Marina made any protest, prior to April 10th, about the existence of the rifle and/ or the pistol? She would testify, after the assassination, that they were living in abject poverty, yet Oswald had enough resources to spray money around on his weapons collection. But did she make any such statement, or did she recall making any such statement, prior to the assassination? And was the abject poverty the sum and substance of her concern? Guns don’t kill people…. abject poverty does.

April 10, 1963— 9: 30 p.m. CST (time not precise). One shot was fired at Major General Edwin E. Walker, U.S. Army, Resigned, as he worked on his income tax returns while sitting near a window. He will telephone Robert Alan Surrey as well as the police, and Surrey will arrive within fifteen minutes, and overhear police conversation as well as press interviews given by Walker….

[There is a big big blurb on this I excluded.]

April 10, 1963— 9: 15 or 9: 30 p.m., CST, Dallas, Texas. Robert Alan Surrey arrives at the home of General Edwin A. Walker, U.S. Army, retired. Aware of people looking in windows on April 8 and the presence of tire prints outside, Surrey spends the evening at Walker’s home and the tire imprint evidence is sought on the morning of April 11. (Testimony of Robert Alan Surrey, 5H 440) Note: Upon Surrey’s arrival, Walker pointed to a hole in the wall and Surrey said, “Oh, you found a bug.” Surrey would also notice that Walker’s right forearm was bleeding slightly. No explanation is given for that.

April 10, 1963— 10: 00 p.m., CST— Dallas, Texas. Marina Oswald “suddenly” discovers a note written by Lee Oswald, which allegedly contained instructions as to what she should do in the event he is taken into police custody. The first item indicated, “Here is the Key to the post office box which is located in the main post office downtown on Ervay Street, the street where there is a drugstore where you always used to stand.” As it happens, the Post Office was at 400 N. Ervay Street (where Warren Commission depositions were taken in Dallas), and four blocks south of there was “Skillern’s Drugs” on the first floor of the Mercantile Bank Building. The fifth and seventh floors of that building were occupied by Hunt Oil Company. The Warren Commission Exhibit volumes begin on 16H 1, and the first item is “an unsigned note in Russian to Marina Oswald.” The contents of this note, when translated by my erstwhile Russian guest, pro-tem, of the editor of this Chronology (and therefore able to be translated by any number of people in close contact with law enforcement, c. 1963), strongly suggest that it was the “Walker note,” left for Marina. It seems an odd and almost bizarre coincidence that the very first item published in the “manual of Oswald’s guilt” was a note providing instructions for what a non-Russian-speaking woman should do on the odd chance that her husband was incarcerated or killed in some unstated event. It seems even more odd that no translation was created for that exhibit— because many other such exhibits are translated. Nor was any handwriting expert consulted to see if the note was written by Oswald— since it was known, via Marina, that she received the note. The note has a notation that looks like “D 30 Jue” on the upper right-hand corner in smallish script. I cannot place any meaning on it. (Commission Exhibit 1, 16H 1) That said, I asked my transient Russian visitor to review a good number of Oswald’s writings in Russian, and while she found a good number of grammatical errors, most commonly the omission of necessary commas, she paused while reading this first document— this possible “Walker note”— and asked how long the writer of the document had been in Russia. I told her, “Two-point-five years, and this was approximately one year AFTER his return.” She told me that Oswald’s Russian— as shown in the note— that beyond the absence of commas, there were a number of extremely well-made connections in words. The Russian language contains constructions “bl” and “b,” which, when they follow certain other letters, are silent, but they change the intonation and inflection of the letter just before them. Oswald had all of them correct, and it seems unlikely that he wrote the Walker note using a dictionary over the span of several days. “Look, here,” my guest said, “many Russians would not get this correct— or this word here— would not be spelled correctly.” She also added parenthetically that “a long, long time ago,” she saw a movie, in Russia, in the Russian language. It was a Russian movie, not an American movie with a Russian overdub, and it portrayed Oswald as, in her specific words, “a very strange man indeed.” I leave it to the reader to draw the necessary conclusions, but it seems bizarre in the extreme that someone who could not spell at all well in English (allegedly his native language) could nevertheless correctly spell difficult if not impossible Russian words. Addendum: Although the first exhibit is not attributed to Oswald, nor specifically to the Walker event, the events immediately following CE 1 are also Walker-related, except for one photo of Oswald, neck-up, in his Marine digs with a helmet, suggesting, of course that he knew how to kill. You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows…. Question: Why would there be a reference to a location where Marina “used to stand”? Finally: Much has been made of the “Walker note,” and Marina, investing all her energy to convict her husband for everything imaginable, made sure that the Warren Commission got the full treatment, with all of the possible “Walker thoughts,” including all of that which Oswald allegedly burned so it did not have to be produced, still had the energy to note that the photo with the hole where the license plate should have been HAD been an intact photo when she saw it. Sylvia Meagher, a first-generation assassination researcher (d. 1989), took an alternative view of the so-called Walker note, and her spin is that it had nothing to do with an assassination attempt on General Walker. Meagher’s only published work (beyond her indices) is Accessories After the Fact, and to this it day remains one of the Chronology editor’s “top five” recommendations (personal works, including this monster, excluded).

Re: April Fools

Re: April Fools

Sun 18 Jun 2017, 2:15 am

Continuing...

April 10, 1963, late evening, Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald returns home, after allegedly firing a shot at General Edwin Walker, sitting in an illuminated window, and missing. “… the day Lee shot at Walker, he buried the rifle because when he came home and told me that he shot at General Walker and I asked him where the rifle was and he said he buried it.’ (Deposition of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald Resumed, 11H 293) Note: This revelation came in testimony in late July, 1964, and not when Marina testified day after day in early February as the Warren Commission’s first witness. That may explain its Pinocchio quality, as the totality of the testimony “evolves” with the passage of time. Of equal or greater import, either Lee or Marina was lying about the gun being buried, unless extreme caution was taken with it. Having been long doubtful of this testimony, the editor of this Chronology purchased (legally), a very cheap, well-used bolt-action .22 in the state of New Jersey, and in the month of May (simulating April in Dallas and simulating the quality of a Mannlicher-Carcano before burial), buried it in the earth for three days. In that short amount of time, damage was done to both the wood and the metal parts of the weapon. It has never been fired. Allow for the possibility that a surplus Mannlicher Carcano would not fare any better, and possibly worse— IF it was, in fact, buried. Marina initially testified that Lee had taken the weapon away from the apartment three days after the Walker shooting, TO bury it, but then amended her testimony that he brought it home after three days. One of Lee Oswald’s challenges, of course, if he buried the weapon that he somehow mysteriously carted from 214 Neely Street to Walker’s home, some distance away, is that Oswald would have first had to get out of any residential area, as he could not very well bury the rifle in someone’s front yard and expect them not to notice.

Secondly, Oswald would have had to been cool, calm, and oh-so collected— which Marina insisted he was not, not even when he returned home without the gun— in order to bury it somewhere and remember the exact spot, in the dark, in order to subsequently retrieve the rifle. For my dime, the whole story stinks from start to finish.

April 11, 1963— time unstated, Irving, Texas. Ruth Paine brought Marina Oswald to her home in Irving, following up her thought on inviting Marina to stay there. It was on this occasion (or 8 April 1963) that Marina told Ruth Paine that Lee had asked her to return to Russia and indicated that Lee was tired of the marriage. (Report of FBI S/ As Bardwell Odum and James Hosty, November 28, 1963, CE 2124, 24H 692) Note: Mrs. Paine testified to this event, but was not asked, “What was Marina’s state of mind that day?” given that we have been asked to believe that she was aware, only hours before that her husband had attempted to murder a well-known public figure. (Deposition of Ruth Paine, 9H, 359) April 11, 1963— time unstated, Houston, Texas. On the day after the Walker shooting, Jack Ruby introduced “Lee Harvey Oswald” to friends in the Escapades Lounge in Houston, Texas, a good distance from Dallas. One of the witnesses to the event, Robert Price, described one of the men as 5’11”, 28-30 years old, with light crew cut, and added that an additional person, unnamed, was a pilot. Note: Someone named Lee Oswald, who had previously applied for unemployment benefits, applied for unemployment benefits in Dallas on the same day. (John Armstrong, Harvey and Lee: How the CIA Framed Oswald, p. 521) It would make some sense that this unemployment insurance applicant was the “historical Lee Oswald,” as he had been fired from his job at Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall, where his work concluded on Saturday, April 6, 1963. The only real oddity is that Oswald was not at the unemployment office when it opened on Monday, April 8, and that he waited until Thursday, April 11. In thirteen days, perhaps because of the Walker incident and a near-brush with the law in which Oswald was nearly caught handing out Fair Play for Cuba materials in Dallas, Oswald would skip town and try to make a new start of political chicanery in New Orleans. The kicker: Not until November 22, 1963, did the alleged assassin truly become “Lee Harvey Oswald.” Although that may have been his birth name, and there is some dissent on that point, he did not “use” that name. To the world at large, he was Lee H. Oswald, so this introduction is either overstated by the witness or overstated, if true, by Ruby, to make sure nobody forgot whom they saw. But why would Ruby do that?

April 12, 1963— time unstated, Dallas, Texas. Having weakened his resume entry as “sniper” by his inability to hit a well-lighted General Walker two days previously, Lee Oswald once again visited the Texas Employment Commission in search of employment. (Affidavit of Helen P. Cunningham, June 11, 1964, 11H 478)

April 10, 1963, late evening, Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald returns home, after allegedly firing a shot at General Edwin Walker, sitting in an illuminated window, and missing. “… the day Lee shot at Walker, he buried the rifle because when he came home and told me that he shot at General Walker and I asked him where the rifle was and he said he buried it.’ (Deposition of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald Resumed, 11H 293) Note: This revelation came in testimony in late July, 1964, and not when Marina testified day after day in early February as the Warren Commission’s first witness. That may explain its Pinocchio quality, as the totality of the testimony “evolves” with the passage of time. Of equal or greater import, either Lee or Marina was lying about the gun being buried, unless extreme caution was taken with it. Having been long doubtful of this testimony, the editor of this Chronology purchased (legally), a very cheap, well-used bolt-action .22 in the state of New Jersey, and in the month of May (simulating April in Dallas and simulating the quality of a Mannlicher-Carcano before burial), buried it in the earth for three days. In that short amount of time, damage was done to both the wood and the metal parts of the weapon. It has never been fired. Allow for the possibility that a surplus Mannlicher Carcano would not fare any better, and possibly worse— IF it was, in fact, buried. Marina initially testified that Lee had taken the weapon away from the apartment three days after the Walker shooting, TO bury it, but then amended her testimony that he brought it home after three days. One of Lee Oswald’s challenges, of course, if he buried the weapon that he somehow mysteriously carted from 214 Neely Street to Walker’s home, some distance away, is that Oswald would have first had to get out of any residential area, as he could not very well bury the rifle in someone’s front yard and expect them not to notice.

Secondly, Oswald would have had to been cool, calm, and oh-so collected— which Marina insisted he was not, not even when he returned home without the gun— in order to bury it somewhere and remember the exact spot, in the dark, in order to subsequently retrieve the rifle. For my dime, the whole story stinks from start to finish.

April 11, 1963— time unstated, Irving, Texas. Ruth Paine brought Marina Oswald to her home in Irving, following up her thought on inviting Marina to stay there. It was on this occasion (or 8 April 1963) that Marina told Ruth Paine that Lee had asked her to return to Russia and indicated that Lee was tired of the marriage. (Report of FBI S/ As Bardwell Odum and James Hosty, November 28, 1963, CE 2124, 24H 692) Note: Mrs. Paine testified to this event, but was not asked, “What was Marina’s state of mind that day?” given that we have been asked to believe that she was aware, only hours before that her husband had attempted to murder a well-known public figure. (Deposition of Ruth Paine, 9H, 359) April 11, 1963— time unstated, Houston, Texas. On the day after the Walker shooting, Jack Ruby introduced “Lee Harvey Oswald” to friends in the Escapades Lounge in Houston, Texas, a good distance from Dallas. One of the witnesses to the event, Robert Price, described one of the men as 5’11”, 28-30 years old, with light crew cut, and added that an additional person, unnamed, was a pilot. Note: Someone named Lee Oswald, who had previously applied for unemployment benefits, applied for unemployment benefits in Dallas on the same day. (John Armstrong, Harvey and Lee: How the CIA Framed Oswald, p. 521) It would make some sense that this unemployment insurance applicant was the “historical Lee Oswald,” as he had been fired from his job at Jaggers-Chiles-Stovall, where his work concluded on Saturday, April 6, 1963. The only real oddity is that Oswald was not at the unemployment office when it opened on Monday, April 8, and that he waited until Thursday, April 11. In thirteen days, perhaps because of the Walker incident and a near-brush with the law in which Oswald was nearly caught handing out Fair Play for Cuba materials in Dallas, Oswald would skip town and try to make a new start of political chicanery in New Orleans. The kicker: Not until November 22, 1963, did the alleged assassin truly become “Lee Harvey Oswald.” Although that may have been his birth name, and there is some dissent on that point, he did not “use” that name. To the world at large, he was Lee H. Oswald, so this introduction is either overstated by the witness or overstated, if true, by Ruby, to make sure nobody forgot whom they saw. But why would Ruby do that?

April 12, 1963— time unstated, Dallas, Texas. Having weakened his resume entry as “sniper” by his inability to hit a well-lighted General Walker two days previously, Lee Oswald once again visited the Texas Employment Commission in search of employment. (Affidavit of Helen P. Cunningham, June 11, 1964, 11H 478)

Re: April Fools

Re: April Fools

Sun 18 Jun 2017, 2:21 am

Continuing...

April 12-13, 1963— times unstated and unsolicited; Dallas, Texas. Marina Oswald indicated she saw numerous photos of Walker’s house amidst a collection of data Lee Oswald had compiled. (Testimony of Marina Oswald 1H 39) Question: If she had just been ‘rescued’ by Ruth Paine the day before, how, on this date, would she have been rummaging through Oswald’s private yet sophomoric collection of spy-wannabe materials? If she was trying to induce spousal abuse, she was clearly on the right track.

April 13, 1963— time unstated and unasked— perhaps for good reason; Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald burned his “notebook” of logistics (descriptions of house, distances, location, distribution of windows) regarding the Walker shooting. He did so by burning his notebook with matches over a wash bowl in the bathroom in the apartment on Neely Street. Marina’s testimony is confused and garbled, as one might expect from testimony being invented as events dictated: Liebeler: “You previous told the Commission that Lee Oswald prepared a notebook in which he kept plans and notes about his attack on General Walker; is that right?” Mrs. Oswald: “I saw this book only after the attempt on Walker’s life. He burned it or disposed of it.” [Yet she will later say she saw him making entries on a regular basis, and she saw him burn it, so why the “or””] Liebeler: “Tell me when you first saw the notebook?” [She would subsequently testify she saw him making entries in it before the shooting.] Mrs. Oswald: “Three days after this happened.” [perjury] Liebeler: “You saw the notebook 3 days after it had happened?” Mrs. Oswald: “I think so.” Liebeler: “How did you come to see it then?” Mrs. Oswald: “When he was destroying it.” [perjury] Liebeler: “Is that the only time you ever saw it?” Mrs. Oswald: “I saw on several occasions that he was writing something in the book, but he was hiding it from me and he was locking it in his room.” [perjury] Liebeler: “Did he actually lock the door to his room when he left the apartment?”

Mrs. Oswald: “The door to his room could be locked only from the inside and he was locking the door when he was writing in the book, otherwise, he was hiding it in some secret place and he warned me not to mess around and look around his things. He asked me not to go into his room and look around.” Liebeler: “You saw him writing in this book before the night that he shot at General Walker?” [questions all based on the a priori assumption of Oswald’s guilt in the Walker shooting, with the only proof being Marina Oswald, a former Soviet citizen who had been cast out of Leningrad for reasons not documented, sent to Minsk, where she met an American and married him— then ratted him out.] They are asking the person who would find him guilty whether or not he was guilty…. Mrs. Oswald: “Not before the night.” Liebeler: “After?” Mrs. Oswald: “No; not before— 1 month before, but not every day, you know, sometimes. I saw him writing on several occasions in that book prior to the attempt on Walker’s life, only I did not know what he was writing.” …. Liebeler: “But 3 days after he shot at General Walker, you saw him destroy the book; is that correct?” Mrs. Oswald: “Yes.” Liebeler: “How did he destroy it?” Mrs. Oswald: “He burned it.” Liebeler: “Where?” Mrs. Oswald: “In the apartment house on Neeley.” Liebeler: “Where in the apartment?” Mrs. Oswald: “He burned it with matches over a wash bowl in the bathroom.” Liebeler: “And you first became aware of this when you smelled it burning; is that correct?” Mrs. Oswald: “I did not see the book, but I saw him writing in this book several times, but after he burns the book he told me what was in that book and he showed me several photographs. Before he burned the book, he showed me several photographs that were in the book. I asked him what the pictures were and he sad, ‘Well, this one is a picture of the house of General Walker’s— his residence.” Liebeler: “And that picture was pasted in the notebook; is that right?” Mrs. Oswald: “No; It was loose in the book— I really don’t remember.” [the standard “Marina refrain”] …. Liebeler: “Did you say anything to Lee when you saw him destroying this book about why he prepared it and why he left it there in the apartment when he went to shoot General Walker?” Mrs. Oswald: “No; I did not. No; I never asked him why he left it in the apartment, why he left his book in the apartment while he went to shoot General Walker. I did not ask him why he left it in the apartment. I asked him what for was he making all these entries in the book and he answered that he wanted to leave a complete record so that all the details would be in it. He told me that these entries consisted of the description of the house of General Walker, the distances, the location, and the distribution of windows in it.” … “All these details— all these records that he was writing it either for his own use so that he would know what to do when the time came to shoot General Walker. I am guessing that perhaps he did it to appear to be a brave man in case he was arrested, but that is my supposition. I was so afraid after this attempt on Walker’s life that the police might come to the house. I was afraid that there would be evidence in the house such as this book.” …. “At the time he was destroying it— he showed me this book after this attempt on Walker’s life, and I suggested to him that it would be awfully bad to keep a thing like that in the house.” Marina then claimed that at the same time, Lee took the rifle and buried it, and then she craftily recanted and claimed the rifle’s interment was immediate: “No; the day Lee shot at Walker, he buried the rifle because when he came home and told me that he shot at General Walker and I asked him where the rifle was and he said he buried it.” …. Liebeler: “Had he destroyed the notebook before he brought the rifle back?” Mrs. Oswald: “No.” Liebeler: “How long after he brought the rifle back did he destroy the book?” Mrs. Oswald: “He destroyed the book approximately an hour after he brought the rifle home.” Liebeler: “After he brought the rifle home, then, he showed you the book?” Mrs. Oswald: “Yes.” Liebeler: “And you said it was not a good idea to keep this book?” Mrs. Oswald: “Yes.” Liebeler: “And then he burned the book?” Mrs. Oswald: “Yes.” (Deposition of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald resumed, 11H 293— 294)

Note: This is a seriously significant exchange, for at least two reasons. First, by suggesting that Marina had NO KNOWLEDGE of the Walker event, she’s off the hook for that one, although she testified shortly thereafter, “I was so afraid after this attempt on Walker’s life that the police might come to the house. I was afraid that there would be evidence in the house such as this book… I told him that it is best not to have this kind of stuff in the house— this book…. At the time he was destroying it— he showed me this book after this attempt on Walker’s life, and I suggested to him that it would be awfully bad to keep a thing like that in the house.” (Deposition of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald Resumed, 11H 292-293) Why would it be necessary for Marina to tell Lee that the book was not a nifty keepsake WHILE he was in the process of destroying it? The reality is that she was guilty as an accessory after the fact— but since she was the Warren Commission’s “star” with her ability to make Oswald into a monster, since he was not alive to do it himself, no charges would have been considered. Secondly, “the tale” takes on added significance because it is most likely that the DeMohrenschildts visited the Neely Street apartment and saw the Oswalds for the last time— and by accident (so we are asked to believe) they also saw the rifle. It has to be considered that the burning of paper and possibly photographs would leave a lingering aroma (especially photos, c. 1963) in such a small apartment and would have been still detectable by the late-night visitors— particularly as there is no indication that the purification burning ritual was carried out as early as dawn. Finally, if the reader goes back to the testimony immediately above, the question needs to be asked, If Marina was afraid that something LIKE THE BOOK could cause problems with the legal authorities, what in God’s name did she think the gun was going to do for anyone’s ability to stay out of jail? There is absolutely no logic to any of this, and if read that way, it seems clear that Liebeler is just walking her into a trap that there is no way out of. As a final thought, a few lines later, Marina would insist, when shown CE 5, that the license plate had been there when she was first shown the photo.

April 13, 1963 (possibly, and dangerous if true, April 14) Lee Oswald retrieved the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle allegedly used to shoot at General Edwin Walker on April 10, 1963, and allegedly buried on that date until its retrieval three days later. (Deposition of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald Resumed, 11H 292) Note: Marina Oswald is unsure, in her testimony, as to the exact time of the retrieval:

“As I remember, it was the weekend— Saturday or Sunday when Lee brought the rifle back home.” (Deposition of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald resumed, 11H 293) Marina Oswald is once again suffering from her ongoing bouts with selective memory; the gun had to be in the Neely Street apartment on Saturday, as that is when Jeanne DeMohrenschildt saw the weapon, and George DeMohrenschildt blandly commented that it must have been Oswald who missed with the shot taken at General Walker. Secondly, had the Warren Commission been aware of its own evidence, they would have taken the two events— the return of the weapon (method unstated), and the DeMohrenschildts’ visualization and verbalization of it— and compared them to Ilya Mamantov’s translation of Marina Oswald’s answers to Will Fritz in the early evening of November 22. The most telling of those comments was that she had never seen anything more than the butt end of the gun, secreted in the blanket, but that she had never seen the gun itself. She saw the entire gun when Lee “brought it back,” she saw it in the closet with Jeanne DeMohrenschildt, she saw it on the porch on Magazine Street based on testimony that she watched Lee work the bolt, and she photographed Lee Oswald holding it. (See deposition of Ilya Mamantov) Note: If there are two facts tangential to the Kennedy assassination that are known to be absolutes and not in dispute, they would be that Walker was lionized by not only the Dallas right-wingers, but throughout much of the rightist South, and second, that he was equally respected and admired by the vast majority of the Dallas Police Force, a group which was believed to be a subset of the Birchers and Minutemen, c. 1963. While that is an exaggeration, there were certainly many right-wingers and far fewer, if any, “liberals” among the group. Yet the Walker shooting, noted in the papers as leaving behind a 30.06 steel jacketed bullet, was unsolved until it was “solved” in the guilt by association mode and the testimony of Marina Oswald. There are too many missing pieces here— if the cops were unable, in what had to have been dogged attempts, to find a body of evidence to seek an indictments or indictments, since the murder attempt was on someone who was very highly thought of by them, how, suddenly, did the “steel jacketed bullet” implicate Oswald, to the exclusion of others, on and after November 22nd? Clearly, it was a day for magic bullets. (media sources) Note: With respect to Lee Oswald’s burning of the written evidence of his planning of the Walker event, photos did survive, including one (CE 5, 16H 5), showing a grainy view of Walker’s home, and including a 1957 Chevrolet with a hole in the photo where the license plate would have been. Adamant as she was in “giving up” Lee for the Walker crime, Marina Oswald was equally adamant that she had seen that photo and it was intact— license plate included— when she saw it. Warren Counsel Liebeler tried to get her to admit to the possibility that the mark could have resulted from a crease or from a hole being made through the photo (which clearly DID happen), but Marina stood her ground on the visibility of the license plate when she saw the photo. It appears in Jesse Curry’s Memoirs, and although unreadable absent some kind of computerized magnification, the photo as shown in Curry’s book DOES include the license plate. The license plate on that vehicle, parked in front of Walker’s house, was “redacted” by having a hole cut in the photo AFTER it left the property room of the Dallas Police. Suspects in this “for certain” photographic alteration could include, but not be limited to Dallas cops, FBI, Warren Commission— but it was not an accident that the license plate in question disappeared from the photo of that vehicle. In the normal course of “accidents happen,” any similar sized portion of that photograph could have been damaged. But the coincidence that a small piece was damaged and had contained the license number is another instance of one “Kennedy coincidence” too many. So when one views the Warren Commission’s “Exhibits,” one only has to proceed as far as Commission Exhibit 5, on the fifth page of Volume XVI, to see that the lies and deceit begun with the words, scripted questions, unasked questions, avoided witnesses— continues immediately into the exhibits. (For Marina’s recollection of there being a license plate visible in the original photo— and how would she be aware except if the photo was intact?— see Marina Oswald’s insistence in deposition of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald Resumed, 11H 294-295)

April 12-13, 1963— times unstated and unsolicited; Dallas, Texas. Marina Oswald indicated she saw numerous photos of Walker’s house amidst a collection of data Lee Oswald had compiled. (Testimony of Marina Oswald 1H 39) Question: If she had just been ‘rescued’ by Ruth Paine the day before, how, on this date, would she have been rummaging through Oswald’s private yet sophomoric collection of spy-wannabe materials? If she was trying to induce spousal abuse, she was clearly on the right track.

April 13, 1963— time unstated and unasked— perhaps for good reason; Dallas, Texas. Lee Oswald burned his “notebook” of logistics (descriptions of house, distances, location, distribution of windows) regarding the Walker shooting. He did so by burning his notebook with matches over a wash bowl in the bathroom in the apartment on Neely Street. Marina’s testimony is confused and garbled, as one might expect from testimony being invented as events dictated: Liebeler: “You previous told the Commission that Lee Oswald prepared a notebook in which he kept plans and notes about his attack on General Walker; is that right?” Mrs. Oswald: “I saw this book only after the attempt on Walker’s life. He burned it or disposed of it.” [Yet she will later say she saw him making entries on a regular basis, and she saw him burn it, so why the “or””] Liebeler: “Tell me when you first saw the notebook?” [She would subsequently testify she saw him making entries in it before the shooting.] Mrs. Oswald: “Three days after this happened.” [perjury] Liebeler: “You saw the notebook 3 days after it had happened?” Mrs. Oswald: “I think so.” Liebeler: “How did you come to see it then?” Mrs. Oswald: “When he was destroying it.” [perjury] Liebeler: “Is that the only time you ever saw it?” Mrs. Oswald: “I saw on several occasions that he was writing something in the book, but he was hiding it from me and he was locking it in his room.” [perjury] Liebeler: “Did he actually lock the door to his room when he left the apartment?”